“The guy who sat

down and engineered the whole railroad idea . . . It still amazes me sometimes

that you can keep something that big, that heavy, on two little old strings of

steel and a little flange on the wheels is the only thing keeping that on. It’s

got all the weight and all that force, but if you bring it up two inches, your

whole day is ruined.”

—Keith

Metheney

Railroad History:

Road Monkeys to

Salamanders

Railroads

arrived with logging. They were the most effective means of transporting timber

off the mountains at the time. Originally brought in to ship logs and later used

to transport coal, railroads were the first commercial transportation to connect

parts of the watershed with the rest of the country.

However, the ease of

building roads and the flexibility of trucking out-compete the steel roads and

have brought the age of railroads to an end. Now, most of the railroads that

once ran up every major stream along the Shavers Fork are gone except for the

roadbeds, sometimes marked with corduroy bumps from decaying crossties. One

exception is the fifty-mile track between Spruce and Bowden, which is still in

use and follows the riverbed. Now a small excursion train hauls tourists instead

of logs or coal through the stunning forest where once logging camps and coal

mines bustled.

Dewing & Sons put in the first railroad on the watershed in the late nineteenth

century. It was a narrow gauge railroad from Lambert Run to the log landing at

Cheat Bridge. This railroad, which was only about three miles in length, wasn’t

connected to any other lines, so a Shay locomotive had to be brought in by

wagon, piece-by-piece. It was later sold with the land to West Virginia.

Cheat Summit

Fort

-

1861–1862

West of where the

Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike (now U.S. 250) crosses the Shavers Fork at

Cheat Bridge lie the remains of a Civil War fort. Fort Milroy, sits at more

than 4,000 feet above sea level, making it one of the highest Civil War

sites in the nation. The fort was built on the farm of an old homesteader

named White, which is why the knob there is called White Top. Ambrose

Bierce, who later became a famous author, was among the troops. He writes,

“. . . It was after this, when the nights had acquired a trick of biting and

the morning sun appeared to shiver with cold, that we moved up to the summit

of Cheat Mountain to guard the pass through which nobody wanted to go.”

There was one failed attack on the fort. General Robert E.

Lee led an inspired but poorly executed plan to capture the fort. He

separated his men into no less than six columns to attempt to isolate and

overtake Cheat Summit Fort and another fort in the Tygart Valley. Three

thousand men were deployed to Cheat Mountain Fort. They were divided into

two groups to surround the fort and

simultaneously attack. However, one of

the regiments encountered a supply wagon and the element of surprise was

lost. Due to the density

of the woods, neither side could estimate the size of the other force,

and 200 Union troops managed to rout the

1,500 Confederate soldiers. Over the next two days numerous skirmishes

occurred, but a coordinated attack was impossible and Cheat Summit Fort

withstood the attack.

simultaneously attack. However, one of

the regiments encountered a supply wagon and the element of surprise was

lost. Due to the density

of the woods, neither side could estimate the size of the other force,

and 200 Union troops managed to rout the

1,500 Confederate soldiers. Over the next two days numerous skirmishes

occurred, but a coordinated attack was impossible and Cheat Summit Fort

withstood the attack.

However, the Confederates were not the only dangers in those

times. Many soldiers died from the cold and measles. Many of the horses died

due to an unusually cold September, and snow began falling as early as

August 13 that year.

The troops

left in April 1862, and the fort was abandoned. An Indiana

volunteer recalled his departure: “With what a light step all started. Soon

on the road turning at the brow of the hill, the Fourteenth took what I

fondly hope is their last look at Cheat Mountain.”

Marker at Cheat

Summit Fort historical site, 2005: “Note how earth was mounded to form the

walls of the fort.”

Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition

Since then, much of the fort and surrounding area have been

lost to surface mining. The major fortification still remains. The

Monongahela National Forest owns what is left of the Cheat Summit Fort. They

successfully nominated it for the National Register of Historic Places in

1990 (Monongahela National Forest).

Surface mining at

Cheat Summit Fort - 1960's

Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest

Same site in 2005. Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition.

Horse Hauls First Engine to Cheat Mountain

Virgil Broughton,

who grew up in Spruce during the 1940’s and ‘50’s, comments on this bit of

railroad history:

Can you visualize

floating logs down Cheat River? Did you know that in 1880 there was a guy by the

name of O’Day that came in here from Michigan in a horse and buggy and hauled an

engine all the way to Huttonsville at the base of Cheat Mountain? And by horse

and buggy, he took it on top of Cheat Mountain to Cheat Bridge where there

wasn’t a bridge and laid a railroad upriver and downriver. That was the old

Staunton and Parkersburg Turnpike up in there. They laid rail and put that steam

engine on that rail and hauled that train on top of that mountain by horse and

buggy. And O’Day floated those logs on the river all the way to Pennsylvania.

Can you visualize it? It’d be hard enough today in an eighteen-wheeler to haul

an engine to the top of Cheat. And if there’d been any mud, they’d be up to

their knees.

Railroad Reaches Cass

Two of the country’s

main rail lines drew closer to Cheat Mountain. The Chesapeake & Ohio line

finally came to Pocahontas County and reached Cass in December of 1900. It’s

interesting to note that there was a considerable local opposition to the

railroad coming in. Some folks claimed trains “carried whiskey, killed chickens

and cows, scared the horses, and threw the teamsters out of work” (Clarkson I,

9).

West Virginia Pulp & Paper was the first company to bring in

a connecting line to the watershed. Wanting to extract the vast stores of timber

on Cheat Mountain, they knew that they had to find a way to get a railroad up

there. It was soon discovered that Leatherbark Run, up behind Cass, was the most

likely spot. That was not saying much. The climb up Cheat Mountain, which

required two switchbacks, was most likely the worst of its time. The grade was

greater than 11 percent at times—most railroads rarely go over a 3 percent

grade. Still, in January 30, 1901, West Virginia Pulp & Paper crested Cheat

Mountain and opened that wild country to extraction (Clarkson I, 37).

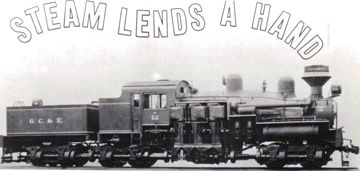

Davis and Elkins’ Coal & Iron Railway

At the other end of the line was Senator

Henry Gassaway Davis who had long dreamed of connecting the Baltimore & Ohio

(B&O) with the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O). In 1900, Davis formalized plans with the

C&O to connect with their Greenbrier Branch in Durbin.

Keith Metheney, a

current track foreman for the Elkins–Spruce–High Falls segment, explains the

creation of the Coal & Iron Railroad:

Senator Davis and

Stephen Benton Elkins created the Coal & Iron Railway as the original line that

went up Cheat, but the Coal & Iron was a subsidiary of Coal & Coke. I think they

built the rail line from Elkins to Durbin in two years, between 1901 and 1903.

They worked on the tunnel up here at the beginning of the mountain and the one

at Glady simultaneously.

It almost took the same

amount of time to build those tunnels as it did to build the rest of the

railroad. And then when they got the tunnels, they connected everything up. It

operated under Coal & Iron just a few years before it was bought by Western

Maryland, and they tied everything together. Of course GC&E [Greenbrier, Cheat,

and Elk Railroad Company], come down from Spruce and tied in with them there at

Bemis.

If I remember right,

Bemis was the farthest stretch for the GC&E and it’s kind of odd to think . . .

Of course, that was before the Federal Regulations

Act (FRA) and hours of service and everything. Under FRA rules you are

only allowed twelve hours in the cab of a locomotive before you have to sign

off, kind of like truck driving. At one time it was sixteen hours, but before

they instituted that it was unlimited. If you stop to think—if you’ve ridden

the Cass train—how slow it goes: top speed nine miles an hour.

Those guys were leaving

out of Cass and doing a fifty-mile run down to Bemis and a fifty-mile run back.

It’s no wonder that when they got done logging the Bemis end, all the trees

around Spruce were ready to cut again. The second growth timber was almost as

good.

The line from Cheat Junction up to Spruce

wasn’t started until 1910, by a newly formed company called the GC&E, a

subsidiary of West Virginia Pulp & Paper. They connected West Virginia Pulp &

Paper’s line with Western Maryland’s and then continued westward from Spruce to

get down to Slaty Fork and the Elk River. In order to do this, they originally

were going to construct a tunnel, but the shale rock wouldn’t support the roof

so they constructed what came to be known as “Big Cut.”

Construction of this line took seven years,

mostly because of the time put into the Big Cut. It too was bought out in 1928

by Western Maryland, who used the line to haul coal out of Slaty Fork area.

Timbering Along the River

Jim White recalls part

of the history of logging on Cheat:

When Western Maryland

took it over, West Virginia Pulp & Paper owned the whole watershed on both sides

of the river. Every hollow, they’d put a railroad up it, and they’d log it out

and pull the steel out and move to the next one—I presume up both sides of the

mountain. Then they bought land on the Elk River, involving Elk Mountain and

Gauley Mountain, so they went through that big cut. They made that big cut in

there so they could get a railroad down to Slaty Fork and down that river.

But I think they finished cutting all that

timber down that river. In 1925, they discontinued their mill at Spruce, and

they made a similar, smaller plant then, along the side of the big mill here at

Cass. Then Western Maryland was interested in the coal that they were mining in

Webster County, and they bought the whole line from Bemis all the way to Bergoo.

West Virginia Pulp & Paper sold that whole railroad, and they had already moved

the pulp mill down to Cass. They still used the railroad, but they paid a bonus

to Western Maryland, because it was theirs then.

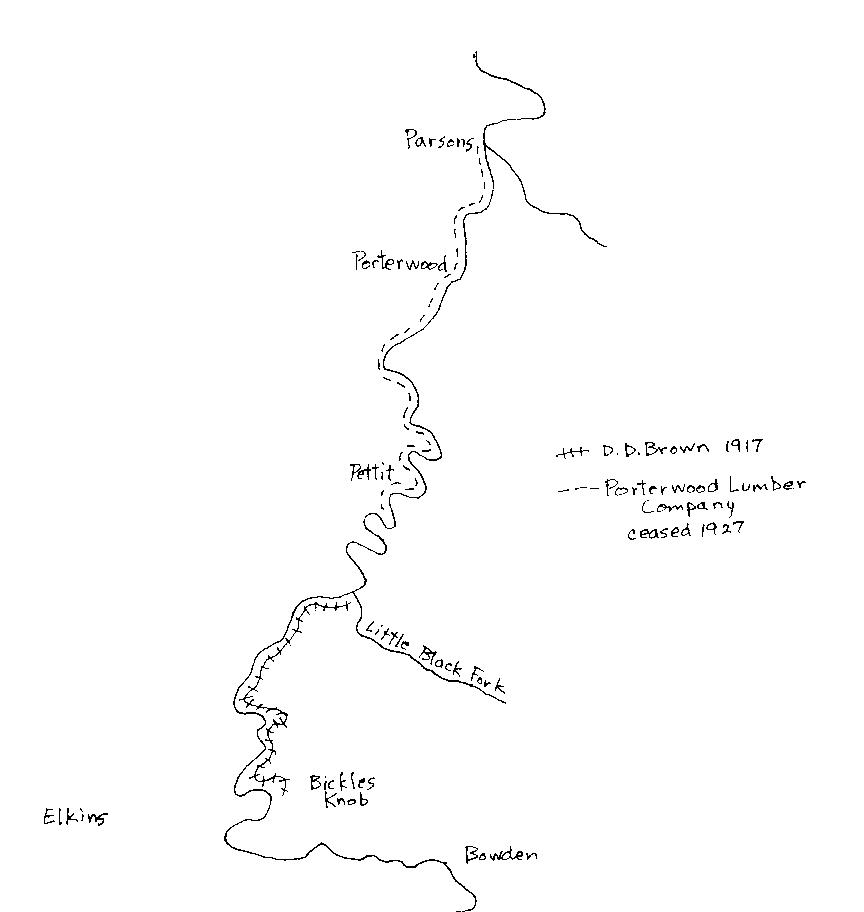

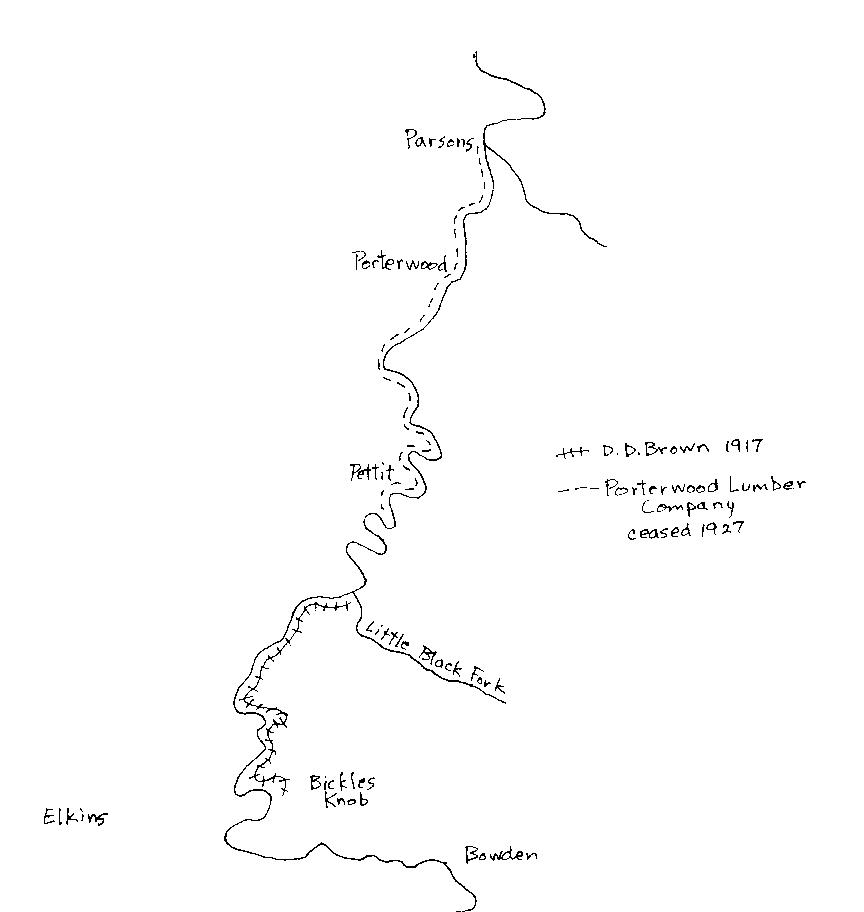

Porterwood to Little Black Fork Line

On

the lower end of the watershed, there wasn’t as much railroad activity.

D.D.

Brown reported putting twenty-five miles of track between Bickles Knob and

Little Black Fork by 1917. Porterwood Lumber Company put in tracks farther

downstream, but they didn’t stay long.

Agnes Wilmoth writes in

her memoirs written prior to her death in 1983:

It took

months to build the railroad from Porterwood to the end of the line up in Little

Black Fork. There were big ledges of rock to go through and no modern machinery

to work with. Drilling was done by hand, and they would work for days before

they would shoot. We have watched many times when it looked like half the

mountain would heave up, then more drilling, more shooting, till it was down on

a level.

All work was done the

hard way, and foreigners done a lot of the grade work: Austrians by the dozen.

They lived in shanties that could be moved as the track was laid. The first

train that came up the river caused a lot of excitement. One engineer was Simon

Losner, and his fireman was Walter Teter. The second train, the engineer was

Wooster Oldaker, and his fireman was Okey Oldaker, his son. The two trains

hauled two trips a day, and each one had a long train of logs. To a bunch of

kids living where they could see the long strips of logs going by, it was better

than a circus. None of the young folks of that day are there now.

Gandy Dancers and Derails on Cheat

The timber between was cut out

by 1927 and the railroad made into a car road, but years of trains, timber

cutting, and the vast quantity of logs will always remain in memory.

Before the tracks were there,

the land had to be graded and molded so that tracks could be laid down. This

backbreaking labor was often done by hand and was certainly not preferred over

logging or driving trains.

In order to get labor, many companies hired black people and newly arrived

immigrants to do the hard work.

On Cheat Mountain,

Austrians and Italians were the preferred workers, appreciated for their

happy-go-lucky natures and pleasant dispositions. These laborers are the unsung

heroes of the industrial revolution, working eleven-hour days, six days a week

for just a dollar a day plus room and board. Amazingly, on this small amount,

many were able to later send money for their families to come join them in

America.

happy-go-lucky natures and pleasant dispositions. These laborers are the unsung

heroes of the industrial revolution, working eleven-hour days, six days a week

for just a dollar a day plus room and board. Amazingly, on this small amount,

many were able to later send money for their families to come join them in

America.

These “Gandy Dancers” (men who laid and

maintained railroad track) were given numbered tags by which they were

identified, paid, and sometimes even remembered on their gravestones. Many of

the immigrants were suspicious of American money when they first arrived; they

had heard stories of people swindling new immigrants and were naturally worried.

Initially, they demanded their payments in gold, which the locals really didn’t

seem to like.

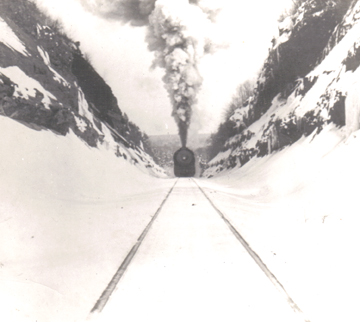

Shay engine coming up the tracks, Cheat Mountain. Photo courtesy

Monongahela National Forest.

-

Here are a couple of “dogtags” that were used to

identify the Austrian and Italian laborers on the railroad. Several gravestones

have been found with only these numbers inscribed in them.

Photo courtesy Phil Miller

Pulp & Paper’s First Shay

Life was rough back then,

especially for minorities, but at least the companies treated their employees

fairly well. They also took good care of their engines. West Virginia Pulp &

Paper decided to go with Shay engines, which were specifically designed to go

over just about anything. Built by the Lima Locomotive Company in Ohio, Shays

were designed in the 1870s, and they were good in the mountains because of their

geared drive, which connected the shaft directly to each axle. This meant that

if any wheel spun, they all spun, which rarely happened. This increase in power

came at the expense of speed, which didn’t matter much in the West Virginia

hills.

Shays also had a rather

interesting appearance: the boiler was off centered in order to counterbalance

the cylinders, which were all located on the right side of the train with the

pistons and gear shaft. All these unprotected moving parts made the right side

of a Shay the more interesting and also more dangerous side.

West Virginia Pulp & Paper’s

first Shay was delivered December 29, 1900. It weighed only forty-two tons with

a wheelbase of twenty-eight feet, four inches. It had eleven-inch cylinders and

a twelve-inch stroke. This small Shay soon came to be affectionately known as

“Old Barney” and it was later used mostly on top of the mountain, letting the

larger Shays do the hard trip up and down Leatherbark Run. Old Barney was

delivered with a straight smokestack, which was soon replaced by a

diamond-shaped smokestack designed to reduce spark emissions from the engine.

-

Four of the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company’s

Shay engines. From left to right they are No.3, 2, 1, and 4. Shay No. 1 was

soon known as “Old Barney” by the railroad workers. No. 4 was the largest of

these engines and was used on the Cass Hill. The other engines were “woods

engines” used mostly on top of the mountain.

Photo courtesy Roy Clarkson

Compare Shay No. 1 with the

largest Shay that ever worked on Cheat Mountain. Shay No. 12 weighed 154 tons

and had seventeen-inch cylinders and an eighteen-inch stroke. This was built in

1921 for $54,034, and in 1933, an additional water tank was built onto the

engine, increasing the weight to 208 tons! This alteration made No. 12 one of

the three largest Shays ever. It also allowed West Virginia Pulp & Paper to make

the run from Cass to Slaty Fork in one trip and to pull a hefty load back up the mountain the same day.

pull a hefty load back up the mountain the same day.

However, in

1942 Mower Lumber Company purchased the Cheat Mountain tract. Mower was doing

shorter runs, as well as transferring to a trucking operation, and the huge

engine wasn’t needed. It was scheduled for retirement but didn’t make it. The

most notable wreck on the Shavers Fork happened just outside of Spruce in 1946.

-

Shay No. 12 in an advertisement. This Shay is one of the largest ever to

be built, and was later wrecked just outside of Spruce.

Photo courtesy Keith Metheny from his grandfather, Clair Metheny.

Shay

No. 12 Wrecks on Cheat Mountain

Tom Broughton, the

engineer on the Western Maryland train that ran into the Shay, gave the

following account of the incident during a 1993 interview:

I had orders to go to

Slaty Fork, and this Shay come up there and was coming down in there from Cass.

He had empties. He could see me, but I couldn’t see him. I hit it with a Western

Maryland 788 going around the left hand curve in Spruce.

Merle Irvin was their

conductor. Barkley was the fireman, and I don’t know the flagman and brakemen’s

names. Good was the engineer. Their fireman, brakeman, and him saw me coming

from up top of the hill. There was a big curve in there, and it come around

Spruce right where the ‘Y’ is, about halfway between the houses. Just below the

school, there’s a crossover in there to connect two tracks together. They had

got off of the engine and was standing over on the right side. It was stopped.

Fireman said “Shay

engine!” I put it in emergency, pulled out there and came upon No. 12. It was as

close as from here to your car. I was going about twenty-five miles per hour. I

took the handle and pulled over like that, and I jumped out of the engine onto

the ground. It hit before I completed the jump, but I was already on the way. By

the time they had hit I was heading out the window.

It was a snowstorm that caused it.

My fireman wasn’t looking out and we was going around a left hand curve. He had

fourteen rail lengths of sight to see that Shay engine, but we was about

twenty-five to thirty feet away from it before he saw it. If he’d told me to

stop, I could have.

The snow was waist deep on the

ground. I come near jumping off on a switch stand. That would have killed me.

Mack Teter was firing; I was engineer, heading west toward Slaty Fork. The Shay

was coming down to come down Cheat River.

It was a hell of a noise. The

town’s people heard it hit. I just stood there and looked. No derail but the big

smoke stack on the Shay hit the number plate on my engine. Also, it bent that

Shay up pretty bad. My engine bounced back three or four feet. Of course, he was

hooked up to a bunch of cars and had the brakes set and everything.

“No Union” Blues

Tom continues:

I was wondering what

they’re going to do to me. In them days you had no union. You didn’t have nobody

to fight for you, and I reckon that’s the reason that made me such a good union

man. I had to take this engine back to the shop track and get another engine. I

just went back over in the yard, told the dispatcher what happened, and he gave

me another engine.

Then, I had to go and

tell the dispatcher and copy orders, change the numbers because I had a

different engine. I was heading to Slaty Fork to help bring the train up. The

other engines had already gone and I was the last one. They went ahead of me. I

went right on down the hill and had two trains up the mountain that evening.

Western Maryland got an engine from Cass to pull it back up and push it down the

Shay track.

My assistant boss, Frank Imes, was

down at Slaty Fork when I went down there.

He said, “What in the

hell did you get into?”

He didn’t growl at me.

The guy in Elkins did. He was the main trainmaster. When they got it back, they

called me and Mack in. He gave Mack his notice, “You’re out of service ten days,

and Tom, yours is thirty days off.”

I said, “How does that

come? He’s the one that caused it?”

“Tom you know the rules.

The book says you’re responsible because you’re boss.”

I said, “I don’t care

about the money or losing the thirty days work, the only thing is I hate to have

it on my record.”

I got on Mack for not looking out.

I yelled a good bit. It made me mad. I never criticized him much but he ought to

have seen the Shay. I always tried to be a good fellow. Just like one engineer

up there who was older than I am. I walked in when they were talking about

me—not about the wreck.

This one fellow got up

and said, “I want to tell all you fellows something: anything Tom Broughton has

to say, he’ll tell you to your face. Don’t forget it.”

Of course, now I can go into Cass

and tell them that I’m the man that run into the No. 12 Shay, and they’ll give

me passes to ride. Everybody wants to know all about it and everything. They’re

tickled to death. I had to sign my name for some of them.

"Just Another Train

Wreck"

Tracks are laid

waste

Twisted Steel, the

roadbed destroyed

Engines and

freight cars scattered like matchboxes

"I shudder"

Cold, wet,

freezing rain

The night is dark

and dreary

No shelter to be

had

"I shiver"

Shouts of the

foreman

Men bustling to

and fro

Confusion

everywhere

"I feel alone"

Roar of the rising

Shavers Fork River

So close to the

wreck sight

Danger haunts

every step

"I pray"

Sparks from the

torches

Their fireworks

light the night

A crane groans

under the heavy load

"I feel so small"

Schedules to be

maintained

Trains to move the

freight

Is it worth the

risk?

"I wonder"

by Kenny Watson

-  D.D. Brown, who has a large collection of history at the West Virginia

University Library noted, “The above picture was taken of an accident on the trussel (sic) below what is now Stuart’s Park on our main line railroad running

from Meadows down the road that goes to Stuart Park and down Cheat River toward

Parsons. This accident occurred when the skidway was about empty and some

careless woodsman rolled a large log down and it bounced over there hitting the

trussling (sic) under the locomotive letting it drop down some 18’ or 20’ as I

remember it. It was brought back up with hydraulic hand worked jacks loaned to

us by the Western Maryland. The locomotive saw much service after that. You

will note we used standard W.M. cars equipped with log bunks, etc. Nearly 47

million feet was brought over this line and sawed at Elkins, W. Va.”

D.D. Brown, who has a large collection of history at the West Virginia

University Library noted, “The above picture was taken of an accident on the trussel (sic) below what is now Stuart’s Park on our main line railroad running

from Meadows down the road that goes to Stuart Park and down Cheat River toward

Parsons. This accident occurred when the skidway was about empty and some

careless woodsman rolled a large log down and it bounced over there hitting the

trussling (sic) under the locomotive letting it drop down some 18’ or 20’ as I

remember it. It was brought back up with hydraulic hand worked jacks loaned to

us by the Western Maryland. The locomotive saw much service after that. You

will note we used standard W.M. cars equipped with log bunks, etc. Nearly 47

million feet was brought over this line and sawed at Elkins, W. Va.”

A wreck from near Stuarts Park.

Photo

taken February 29, 1912. Courtesy Roy Clarkson

Hangovers and Log

Spills

Jim White remembers

hearing about one wreck long ago that was particularly interesting:

The

evening train run up there (Spruce), and it was about suppertime, so they would

eat supper and stay in the bunkhouse for the night, and then they’d bring their

loads back down. They made a bunch of home brew—somebody did up there—and the

crew got drunk. The next morning they started bringing a load of logs out of

there, and they weren’t too capable of handling the thing, and so the train ran off.

They knew that on a curve right down below where they were headed for, that that

thing would upset.

and they weren’t too capable of handling the thing, and so the train ran off.

They knew that on a curve right down below where they were headed for, that that

thing would upset.

The engineer threw the engine in reverse, but

it just shoved it right down the track. It didn’t slow down. It was just sliding

with all them logs behind it. And the brakemen, they was so boozed up, they

didn’t get all the brakes set on it. They were in a bad situation so they jumped

off. And on that curve, they lost all the logs or most of them. They upset into

the creek, but the engine went on down. So, as they was setting there, looking

at the disaster, all the logs upset in the river, and here comes the engine up

the track. It had gone down until it stopped, and it was in reverse, so it come

back up.

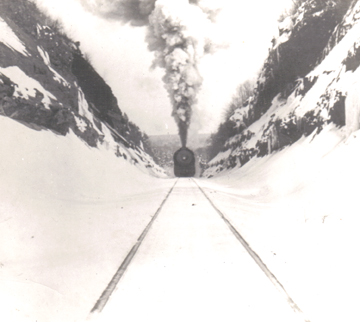

Tunnelwreck1&2: This unusual wreck happened inside the tunnel between Bowden

and Elkins. The cars had nowhere to go, and often forward against each other.

This wreck was one of the worst on the watershed, simply because of the

location. Photo courtesy Keith Metheny from his grandfather, Clair Metheny.

Fast 700 Series

When Western Maryland bought up

the railroad in 1928, they were using the line to haul coal off Cheat Mountain

to the eastern seaboard. West Virginia Pulp & Paper used the same line from

Spruce to Slaty Fork, which is where most of their land holdings were. Later,

Western Maryland used the same line to get coal from as far away as Bergoo.

Because of their extensive holdings outside of the area, they didn’t choose Shay

engines but instead went with the 700 series trains.

Pat Dugan, a long-time

railroader, recalls in a 1993 interview with Phil Miller:

Western Maryland brought

in with them a new age of trains in the area also, the much larger 700 series.

These trains were not as powerful as the Shays and couldn’t pull as much weight,

but they were faster. And since Western Maryland had so many of them, they

simply had to group them together to pull sometimes-massive loads of coal.

What the steam locomotive could

do! What’s a small wheeler against the Shay? We never could compete with the

Shay engine. A Shay was always good for one coal car or more than what a steam

engine could pull. One steam engine out of Slaty Fork, to make it easy for you,

could take eight small cars, which was fifty tons each; take that from Slaty

Fork to Spruce, now that was on a good rail.

In the wintertime when

the leaves were down, the rail was wet. You had snow and sleet and all and you

had to drop two cars off of that—with the Shay you didn’t. A Shay pulled the

same amount of tonnage in the wintertime as it did in the summertime because of

the way it was geared down. There was no traction motion or any loss time with

the wheels slipping, like what you would have on a steam engine. I know that

sounds funny because both of them are steam engines, but that will help.

What happened was we had the

770-class locomotive in there first. We had to change all the shoes and wedges

so that the engine could make the curves. The Shay had a wider maneuverability

on the boiler that could go around a curve. We had to make it up on the shoes

and wedges. We went in with the 770 class. We took two high wheelers in there to

begin with. The high wheelers numbers consisted of the 750 up to the 756; 770 up

to the 80; and then from the 80–89 class, them was low wheelers: smaller wheel

circumference and it made a better working deal all around. When you say what

happened to the engine power, the Western Maryland Railroad leased those Shays

from over at Cass. They belonged to the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company. The

Western Maryland Railroad only had two Shays.

Switchbacks, High Falls Curve, and Bear on the Track

Keith Metheney recalls

some of the reasons why the 700 series was so popular on Cheat Mountain:

The 700 series

locomotives were—they had different classifications—being anywhere from H-6 to

H-9 -- H-6 being the smallest. A 2-8-0 wheel arrangement is basically: the 2

designation is the pilot wheels on the locomotive, in the front; then there are

four driving wheels; and the zero is in the rear of the locomotive. The 700

series was the largest classifications of 2-8-0s that you could run up the

mountain. They were the H-7s. The H-9s were the 800s, and they made the run from

Elkins to Cumberland.

They were a little bit

bigger, a little bit heavier, but they had a longer tender, and because of that

longer tender for longer hauls, it wouldn’t go around that mountain and get

around those curves. When the Western Maryland bought the line, they

straightened out a good bit of that track, but at places like High Falls Curve,

what we call Point Curve, which is below High Falls, and above High Falls a few

miles is Switchback Curve.

High Falls is actually

the sharpest mainline curve in the nation. It’s thirty-three degrees, and

basically you’re horseshoeing on yourself. The 700 series were the largest

locomotives that could actually bend around those curves, so Western Maryland

was limited to what they could do. They actually had to rebuild all the

seventy-ton coal hoppers that they purchased and rebuilt them into fifty

five-ton car hoppers.

Bear

on the Tracks

Western Maryland was the main

operator on the Shavers Fork, owning all the rail line from Bowden to Summit

(Big Cut). This line soon became known as the West Virginia Central Railroad (WVCRR).

They owned the town of Spruce and ran it as a railroad terminus for a while,

until they moved operations to Slaty Fork in order to get a couple more miles

out of the trains everyday. Some of the old folks who lived in Spruce had a

wealth of stories to share about working on the railroad in those days.

Ed Broughton once killed

a bear with his train:

Did anyone tell you

about the bear I killed? We was going up to Spruce. I was firing then, and a man

said, “A bear, a bear, a bear!” She come up out of the river, and she run right

under the cylinder, where you drain the water out before you start the engine.

When it kicked that lever over, she knocked the steam out. Your valve’s on top

of the cylinder: that’s what’s called a spool valve.

Steam comes from the

super heater header into the center of this valve, and that’s steam that hasn’t

been used, it just comes out of these pipes. When it’s used in exhaust, it goes

back out the end of that valve. And that’s exhaust with all that steam going out

that spout, and that pulls this lever. He went right in under this cylinder and

knocked them levers.

I looked and said, “He

didn’t come out!” I could see past. It was night but I could see. I said, “Look

to see just where we’re at so we won’t make a mistake. We’re going to stop when

we come back.”

Charlie, he knew the road better

than me because he’d been working it for years when I was on the track up there,

so when we got back, he said, “It’s around this next turn, Tom.”

I said, “You just watch

everything,” I said, “I’m going out on the front end, and I’ll take care of the

air.”

Before I got down to it

I seen the butt. I reached up and got a hold of the angle cock—it lets the air

through in and out—I got what I thought it would take to stop. We got within an

engine and two car lengths and I seen it lying over a sinkhole.

When the engine almost

stopped, I stepped off the front end. I told the brakeman, “She’s laying right

back there.”

He come off that

engine—he was city boy raised—and he come off of there running, got ahead of me.

I let him get pretty

close to the bear and said, “You know the bear might not be dead!” And I scared

him. I went and got a big long limb and went around the bear and it didn’t move.

“She’s dead.” I keep saying she because she was a she, but we didn’t know it

then.

I told him to hand me

the stoker pole, and we run it through the hide. The train had cut all the meat

in two. The hide was holding it together, and I don’t know how many wheels run

over it, but there was a big hole in that hide. The other side was cut as bad as

this side but no hole in the hide.

We put that poker in there and

drug her back down to the front end of that engine, told the old man to get off

and come help us. The brakeman, I think, got up on the engine; the old man got a

hold of her head and we drug her up on top of the train. When I come in I

stopped at the station, took her off. It was getting daylight, and before I got

out of there with her it was daylight. I put her in the car. I had a little

building below the house. I hung her up in there. The whole crew came out with

me. We ate it. It’s pretty good meat, but there was that much fat on the hind

quarters. The hindquarters were half fat.

I’ve

still got bear grease at home that I collect to put on my leather boots to keep

them from leaking. If you save a little jar of that fat, get the grease, set it

up, it won’t spoil. And if the kid got the croup, give him about a half of

teaspoon of that warm and that would stop the croup in less than thirty minutes.

Coal-Fired Steam Engines

Western Maryland, which

primarily hauled coal, loved to use the coal-fired steam engines: that way they

got their fuel for free and cut down on overhead. But diesel engines, with their

increased power and drastically reduced maintenance needs, began replacing the

700 series in the late 1940s.

Jim White explains:

You see they didn’t know

anything about diesels then, that’s why they used steam. I remember when they

used those old tiny engines up there. I don’t see how the railroad ever

held them up, but the diesels clear outclassed them. That was the kind of

engines they used to haul 100 cars of coal up the railroad all the way from Bergoo, and they would use about six of them heading up to Spruce. And Mr.

Canelli, he was a sawyer, and then when he retired he worked in the company

store, just as a handy fellow, and I went out and listened to his train stories.

And he said he got into the wrong profession because he loved those railroads.

And he used to go . . .

he’d get into the supply truck—see the company had a store in Spruce and they

had one in Slaty Fork—so he would bum a ride on the supply truck to go over to

Slaty Fork just to see the coal drag up out of the Slaty Fork River.

He said, “You’ve never

seen nothing until you’ve seen them hauling all that coal out of there.” And

what they did there was they would leave all of the engines but one at Spruce

because it was all downhill there. They had to keep those things coaled up all

the time. They had a maintenance place up there so that was the people that

lived there after they turned the town over to Western Maryland. They kept all

their railcars maintained there. That’s what I remember from when I was up

there: they still were firing those big engines.

They had a school there.

I remember the last school teacher that they had up there—she was a Blackhurst

girl from over here—and I know, you come down on Friday evenings she’d ride

down, and then on Sunday evenings she’d ride back. But then the diesels got back

in; they could pull a big load of coal up Bergoo. They still needed several, but

they didn’t need water for those things and their maintenance. They didn’t have

a maintenance plant for them. The maintenance on those steam engines was

tremendous.

Working

on the Tracks

The trains didn’t run

themselves. There were many levels of work on the railroad, from brakemen to

engineers and track crew to yard foreman.

Kenny Watson describes

his experience as a machine operator:

It was

hard work. The railroad was hard. I started off as a trackman, and I worked. I

think at that time, and I guess it is the same way today, we bid on jobs. And

the man with the most seniority got the position. When I bid on a chauffers

position—I received what is called chauffer rights—and I was on the seniority

roster as a chauffer.

A chauffer drove the rail trucks. You took the

rail crew out in the morning and back in the evening. It was really no break,

you drove while everyone else just slept. It was a few cents more on the hour,

but it was a step-up as you were trying to build your career. They had B-machine

operators [the next step up] who ran something that you would push and had a

motor on it. They would lift the rail, pull spikes or do other tasks.

I finally got my

B-Machine—I don’t remember where—in Parsons, I believe. When I worked in

Parsons, I worked in a section gang and we took care of the track almost into

Luke, Maryland, and from there to Highland Park (on the outskirts of Elkins). It

ended about where the seafood market is on route 219. There were usually about

five men in a track gang: a chauffer, foreman, and three trackmen.

Once, I took a piece of machinery

up from Elkins and there was a fellow riding with me . . . and we were up around

Bowden—the machine was actually a spiker, a spike railer. It was pitch black

and I was going slow and trying to figure out where I was at on the track, and I

said, “Are we going too fast?”

And he said, “We’re not

even moving.”

I said, “Bull, yeah we

are.”

He said, “No we’re not.” And sure enough, the

motion, you know, after riding that machine for so many miles, we didn’t notice

that we were not moving at all and had not been for five minutes or so.

One time, I was running this

machine called a scar fire that had an arm that stuck out a pretty good ways.

When an old tie was pulled out the machine would scratch out the tie bed. So we

were moving machinery from Elkins to Slaty Fork going up the Shavers Fork River.

We were at the tunnel,

and I said to the mechanic, “Man,” I said. “This arm is sticking out a good

ways.” And this guy, he would not do anything if he didn’t have to . . . and I

said, “Boy,” I said. “This is really close!”

He walks over—we hadn’t

started into the tunnel yet—and he said, “You’re not going to have any problem

with this.”

He walks over—we hadn’t

started into the tunnel yet—and he said, “You’re not going to have any problem

with this.”

I didn’t want to get

stuck in there because we had moved machinery up there before. We had moved up

in that country without lights

to where you didn’t know where anybody was.

So I said, “Man, I don’t

want to get stuck in this tunnel. You know, it’s pitch black in there.”

He said, “I’m telling

you.” He said, “You’ve got plenty of room.”

So I started in there,

and in the tunnel, it makes just a slight curve, and I could see sparks start

from that arm. I thought, ‘Oh no.’ So I just held it down because I thought I

might just drag it through, and . . . no, it wedged me in there. There I sat in

this pitch-black tunnel. And Larry, he was the mechanic, he come in there and he

took that arm loose and lay it back over. I just knew it. I did not want to get

stuck in there with machinery coming behind!

-

track crew: Western Maryland track crew photo

taken in 1963. from right to left is Lee Sharp (track foreman) Grady Doyle, F.K.

Dorie Powers, Walter Smith, Edgar Doyle, Clarence Metheny and Ted Raines.

Photo

courtesy Dorie Powers

Spruce

Repair Shop

Bud Sanders tells about working

in the repair shop in Spruce:

The major jobs would be

done in Elkins. Occasionally, up on the hill in the summertime, the tire would

slip off. You had to heat the tire that went on the wheel. You had to heat it

and expand it then put liner around it, caliber [calibrate] it. Then when it

would cool off; it would tighten up. A lot of times in the summer, if you didn’t

get it right here in Elkins, it would get real hot and they’d slip off. Boy,

that was a job.

You had to take that big

tank—practically carry it—because you know up the railroad track there was

nothing with a freight train there. Your air hose, you’d have to hook on the

front of the steam engine, hook up your air system and get your great big round

ring that went on the wheel. You had the kerosene tank and your air. The ring

that went around there had a thousand little holes in it where the kerosene

would come out. You’d take a torch and light that and heat the tire. When it

would get hot, you’d put it back on and put a piece of liner around it when it

cooled off. These were driving wheels. They had steel tires on them.

When you’d get a high

flange or the tread would wear down, you’d take them off and scrap them and put

on a new one. Ever’ so often when the flange got sharp—you had about a two-inch

flange and on the railroad tracks they’d get real sharp—maybe only about an

inch, bring them in and take about that much cut off of the tire so that you

could make a new flange in the machine shop, then take them back out.

A new set of steel tires

would probably last four or five years. When they put the brakes on it would

flatten the tires. You had to get a grinder and grind the flat spot out of them.

It was a mess. Just grind it down. If you didn’t, it would wobble. You hear a

lot of steel hopper or coal cars where they put the brakes on and drag them.

They go up here and you could hear them.

Riding Rails and Negotiating

The other team of workers

actually rode the trains.

Tom Broughton explains

some of the hierarchy on the train and who had which responsibilities during the

1950’s:

When Frank Imes got

killed, they hadn’t moved to Slaty Fork yet. He still lived at Spruce. He died

in the hospital before they could operate on him. The train run over both legs.

He was a railroad man and he used to work for the Western Maryland when he was

real young on the new line, then he come up and went up to Cass and asked him

about a job. He was hired as a brakeman. At noon they seen that he was a good

trainmaster and made a conductor out of him the same day.

Here the conductor is the boss of

the train. To the engineer, he gives the signals and goes and copies the orders.

Nobody has say over the engine, only the engineer. Nobody else can run that

engine except the fireman to get from an outlying point to a place with a

telephone, but the conductor would have to send right over and tell him how fast

or how slow to go. That was in the book of rules. The engineer was responsible

when he was there. The conductor was over all the trains. In the absence of the

conductor, the engineer was over the brakeman and the fireman.

I served in that for a while—the

state legislature and the brotherhood—I was elected for that. When I went

down there, they elected me then in the main lodge of the legislature. That’s

the railroad men, had nothing to do with the state. But we negotiated, and we

would take it to the state. As I told you, I represented the men about sixteen

years, but then I made local chairman who does all the negotiating for this part

of the railroad and the union.

I’d meet the trainmaster

and if I couldn’t settle with him, I’d meet the superintendent, then ride it

farther on down the road. But I did pick up a little knowledge in some of this

stuff. I didn’t finish high school, but I took an ICS course in Scranton,

Pennsylvania. As far as education, I didn’t have too much but I had good horse

sense. I really enjoyed my work. The last ten years on this road between here

and Cumberland, I qualified one fireman right after another to handle trains. As

soon as I’d get one trained, the boss said, you get your butt off there and get

onto something else, and then he would put another one on there.

Streak

of Fire on the Track

In his

memoirs written in 1976,

Earl Cane related what work was like for the early brakemen

before they had more modern equipment with which to work the brakes. This was

possibly the most dangerous job on the railroads:

You had to

have your wheels right up to the sliding point—lots of times they did slide.

Kept a conductor and brakeman busy going back and forth, checking them and

getting them started rolling again where they were abiding. You didn’t get cold

after you started off that mountain. They worked you from there to Cass.

You’d come up the train from the

back, setting and adjusting brakes, crossing logs coming towards the engine, and

then you just stepped off the stirrup. While on the ground, if you saw a wheel

sliding, you would catch on it and get on there. If you didn’t see any sliding,

you’d let her come down to the end car and catch the end car out. They never

slowed down for you.

After it got dark, put lantern and

hickey in your hands just anyway you could carry them. It was pretty hard to

climb over logs a lot of the time. At night, you could just see a string of fire

from those brakes. A soft brake made a streak of fire—just like a flint. If the

brake shoe was hard, it wouldn’t make so much light. Sometimes they’d get them

soft in the foundry. Boy, they’d just make a streak of fire! I don’t know if you

could read a newspaper by them. You might if you were along close to the

railroad. You might have done it.

Sometimes we had pretty good loads

to cross and sometimes they’d be a son of a gun to get across. They were a son

of a gun all the time when there was ice or it was raining, sleeting or snowing.

Crossing between cars, you had to

climb up the end—had to go down one stack and climb up the other. If the end was

too straight that you couldn’t get to the end, you stuck your brake wrench in

between the logs and came up around and went up the side. The conductor

generally took an extra car and brakeman had three cars. For the extra one next

to the engine, the conductor could let it run wild if the other brakes were

holding. Didn’t set a brake on the closest car to the engine.

It didn’t

take long for shoes to wear out—ten miles from the ‘Y’ down. One trip would wear

them pretty good but they weren’t replaced every trip. They would make several

trips. (Earl Cane Memoirs)

Tale

of a Runaway Engine

Pat Dugan relates a scary story

about a near wreck in the 1940’s:

They would tell you

that’s how I almost lost my job: catching a runaway engine. I never will forget

being sent from Spruce to Elkins and being on trial, but that was three 7’s.

What happened was, the river turn come in, and Simmons hollered at me—I was

standing opposite of the boarding house in Spruce.

He hollered up, “How are

you, Pat.”

I yelled back, “Okay,

how was your trip?” Took my eyes off the engine, standing on the ground. My

labor had gotten up on the right hand side of the engine, cracked the throttle a

little bit. He thought he could get back down off the engine and run ahead of

the engine and catch the switch. When I looked up, the engine kept getting more

momentum, coming back. I thought, ‘well hell that damn thing is running away.’ I

ran across, pushed Sye Simmons out of the way, ran across, grabbed the grab

iron, and it drug me.

By that time it was going that

fast. It drug me along the ground. I didn’t have no power to throw my legs up

over the water tank, the water valve and all, and when I got back right almost

to the water tub, all I could see was this driver in front of me. I didn’t know

when it was going to hit me in the stomach. The Good Lord was with me, and

nobody needs to tell me he wasn’t. My foot dropped down and hit a switch tie,

throwed it in the air with such force that it knocked the heel off my shoe, but

it did throw my leg up and over the water tower so I could get back up in.

Lee Sharp and them will

tell you that they thought I was dead. But I was able to get up in the cab,

throw the automatic brake valve on and I stopped the train, just nine foot from

the derail, the end of the spur. It was all agreed upon that nobody would say a

damn word about it. That’s something I shouldn’t have been doing. Sure, it was

railroad company property and everything, and I thought I could do it, but I

could have lost my life at the same time. I never will forget what Mr. Wolfe

told me across the desk.

He said, “If it hadn’t

been that I know you, knew your family and your railroad connections, I’d fire

you in a minute.” He said, “Pat, never forget we can replace an engine, but we

can’t replace you or anybody.” It wasn’t the idea of being big about it; I

thought I was doing the right thing by trying to save company property. I

thought I was doing the right thing but I wasn’t. I never will forget the look

on the man’s face. He meant exactly what he said.

He said, “I wouldn’t

even think the second time. Who in the hell did you think wasn’t going to tell

this?” The man that I saved the damn engine for was the man that couldn’t get

back to Elkins quick enough to tell them. His name was Buck Poling. He’s dead

and gone, but he didn’t realize what he was doing.

Stoking

the Fire with a Wooden Leg

Terry Grimes, who operates

Grimes Logging, tells an interesting story of a man who worked the firebox on

the trains for West Virginia Pulp & Paper:

I do

remember my dad talking about—and I don’t remember his name, I’m embarrassed to

say—but he had a wooden leg from up above his knee. His job was he fired the old

boiler on the steam engine, and you know, you would throw the slabs in. What you

would fire the engine with was the old slabs from the saw mill—what we have

today is called a ‘chipper’—we grind that up and send that to the paper mills.

But back then, that was

a waste or an off-fall from the logs, and I remember my dad talking about him .

. . he would throw them slabs in that old boiler of the steam engine, and as

they burnt down you would have to keep pushing them down into the old firebox.

Well this gentlemen, he would just take his old wooden leg and push them ends

that wasn’t burnt back into the firebox, and then he just whittled out a new

leg, is what he done.

Whenever he burned out a

leg and it got too short for him to walk on, he’d sit down and whittle out

another leg and he’d get it strapped back on. That was his job. It didn’t

consist of a lot of walking because he just had to stand by the firebox, but he

burned up several legs in his time by that firebox. He had no shoe or nothing,

but just the end of the peg.

Age

of the Railroad Winds Down

The age of the railroad was

coming to an end. With modern equipment making road building easier and cheaper,

trains simply could not compete in short hauling freight. Many train companies

switched over to long-distance  hauling, which made the line over Cheat Mountain

more or less obsolete.

hauling, which made the line over Cheat Mountain

more or less obsolete.

During his final years

with the railroad, Kenny Watson worked on the stretch between Elkins and

Cumberland. The company instituted a series of changes aimed at streamlining

operations through updated communication systems. He says,

“About the time we got all this automation

started was when the whole railroad was phased out.”

Rails

to Trails

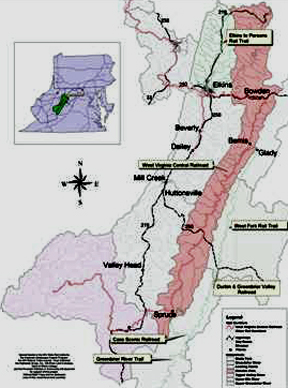

There

were more changes ahead. In 1993, West Virginia Central Railroad filed a

petition to abandon the rail line. After a brief struggle to keep it open, the

last coal was transported over the line in December 1994. In 1997, the West

Virginia State Rail Authority bought the line. It lay dormant, with some

informal traffic as theft of the rail ties for scrap metal.

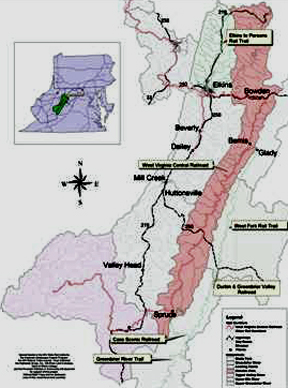

-

A map

outlining the watershed, (in salmon color) and the railroad lines on the

watershed. As you can see the West Virginia Central Railroad (in red) covered

most of the Shavers Fork.

Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition and Canaan

Valley Institute.

In 1998, Mark Tracy rode

the entire track between Big Cut and Elkins on a bicycle specially outfitted for

use on the railroad. He assessed track damage so that the railroad could be

repaired, and he assessed the possibility of creating a rail-with-trail for

recreation. A Davis and Elkins College student intern, Mark’s project was funded

by a grant through the Shavers Fork Coalition.

-  Mark

Tracy, a current Shavers Fork Coalition board member, on his bicycle

outfitted for railroad travel. Mark writes about the rail-bike in his journal,

“The rail-bike is a slow but steady machine. It feels

unstable at any speed above a dogtrot. The book states that it can be ridden up

to 25 miles per hour but is safe only up to eight to twelve. I feel that the

stated speeds are too fast and I doubt if I exceeded five miles per

hour.” Photo courtesy Shavers Fork

Coalition

Mark

Tracy, a current Shavers Fork Coalition board member, on his bicycle

outfitted for railroad travel. Mark writes about the rail-bike in his journal,

“The rail-bike is a slow but steady machine. It feels

unstable at any speed above a dogtrot. The book states that it can be ridden up

to 25 miles per hour but is safe only up to eight to twelve. I feel that the

stated speeds are too fast and I doubt if I exceeded five miles per

hour.” Photo courtesy Shavers Fork

Coalition

June 24, 1998

I pick up the key to

Snowshoe’s gate and then proceed to the USFS [United States Forest Service] gate

at Old Spruce.

At the Twin Bridges (Bridges nos.

374 & 375) I find an earlier abandoned rail grade that followed the bend in the

river rather than bridging the river as today’s railroad does. Also, the

concrete abutments of Bridge 374 are in very poor condition with concrete

shifting and structurally significant cracks extending from top to bottom.

While approaching MP 87, I hear a

loud roaring and clanking noise that puzzles me until I hear the whistle of the

Cass Train as it reaches Old Spruce. I am at least two miles away but I can hear

the train and see its smoke. I ride on through Spruce and then start up the

grade towards the Big Cut. Again I hear noise coming from ahead and when I

arrive at the Big Cut there is a crew working cleaning out the material that is

constantly sliding down from above.

The

red shale that the Big Cut traverses is of the Hinton Formation of the Mauch

Chunk Group. This red shale is very erosive and presents a continuing

maintenance problem as it slides down to the railroad. At work here is a

motorcar for crew transport, a rubber tired backhoe, a Hi-Rail Grade-All, and a

Hi-Rail dump truck that dumps to the side. There is a large amount of rocks and

shale lying in the bottom of the Big Cut and the workers estimate that they will

be working here for a week before they are finished.

As I enter the Big Cut, its

100-foot-high walls reduce the amount of sky visible and I am unable to capture

GPS data. The ‘trail potential’ here is ‘no room for trail’ due to the drainage

ditches needed on both sides of the railroad. These ditches must be extra large

and deep in order to accommodate the material that slides down from above. I

proceed on to MP 89 where I shut down the GPS data-logger without accurately

capturing its position. I then turn around and ride back to Spruce, fold up the

outrigger and return to the truck.

Future of Railroads

The railroad’s future looked

dim—a ghost line of stories, memories and little else. However, an interest in

operating the line as a tourist line began to grow. The State Rail Authority

leased the operation of the line to the Durbin and Greenbrier Valley Railroad.

The New Tygart Flyer and The Cheat Mountain Salamander started running

passengers up and down the length of much of the old West Virginia Central

Railroad.

Keith Metheney shares

how he came to be involved with the operation:

I found out, by reading

the paper that John Smith had gotten the contract, and I didn’t really know him,

hadn’t even been to Durbin to ride that train. I just happened to be down there

sitting one evening, thinking there might be someone to talk to. I was down

there for about twenty minutes when John Smith and his wife Kathy pulled in. I

had some old pictures with me of that old locomotive and got my camera out and

started walking that way. I laugh about it now because I must have looked like a

‘rail fan’ and was gonna bug him, you know.

I got to talking to him

and, of course, he took me in and showed me the engine. It just so happened they

were doing a freight run and he invited me to go with him. During the whole

operation there, I made a comment to him, asked him if they were doing any

hiring. He told me not at the moment; they were just starting out. But I did

volunteer—I had Sundays off, my only day off—and I volunteered Sundays on the

passenger train when they started running it.

I got to talking to him

and, of course, he took me in and showed me the engine. It just so happened they

were doing a freight run and he invited me to go with him. During the whole

operation there, I made a comment to him, asked him if they were doing any

hiring. He told me not at the moment; they were just starting out. But I did

volunteer—I had Sundays off, my only day off—and I volunteered Sundays on the

passenger train when they started running it.

He called me one day and

told me he had a track foreman job, and did I want to take it? I said yeah. So I

started from that—late ‘99. I’m pretty sure they had the permit in late ‘98. It

took most of ‘99 to get equipment and get things going.

The Cheat Mountain Salamander re-loading passengers

at Spruce. The railbus runs from Cheat Bridge to High Falls, and from Cheat

Bridge to Spruce from May through October.

Big Cut, High Falls

Keith continues:

My main job is track

foreman on this end. I take care of fifty-one miles of track over here and the

eleven miles of track over to East Dailey. The way I understand it, I’m track

foreman for the whole eighty-nine miles but this is my inspection and my

maintenance section. There’s another guy who works from High Falls up to Old

Spruce and High Cut. But if something goes on, I’m usually the first one they

call—especially this year. The bigger the operation gets, the more work needs to

go into it. We are all working to make it better—improve it and make it more

interesting and more enjoyable.

This year has been a lot of tree

cutting, and some of them are pretty good trees. As a matter of fact, about four

miles above Bowden is what they call Woodrow, and that’s milepost 42. Well, this

was about 41.2 and there is a place in there where there are some rock

cliffs—they are right next to the tracks. They’re really rounded. It’s actually

a nice formation of rock because they are smooth. But the lower end of them,

right as you are coming around there on the train, is pretty rough rock and a

big old white oak fell down and off that cliff.

I had to stop the train

for it. I had been cutting it and the train came up. Those guys jumped off and

helped throwing branches and clearing stuff away. We realized when we had

cleared a bunch of those branches away that the tree was only balancing on a

limb about six inches around. We could have cut a piece off and got the train

by—there also had been a couple of rocks knocked on the track—and it took four

of us to move it, but we used 15-ton jacks to roll the thing over.

The passengers had a

real good show watching us with steel line bars and jacks pushing this thing

over. We just made the decision that the whole thing was unsafe. Of course, we

turned around, and everyone was still happy. No one asked for their money back

or anything. I don’t want to say we’re not in this for money because if we don’t

make a profit, it doesn’t happen. But like I said, we all want to see something

done to improve the area.

The passengers had a

real good show watching us with steel line bars and jacks pushing this thing

over. We just made the decision that the whole thing was unsafe. Of course, we

turned around, and everyone was still happy. No one asked for their money back

or anything. I don’t want to say we’re not in this for money because if we don’t

make a profit, it doesn’t happen. But like I said, we all want to see something

done to improve the area.

Being a track foreman, I could

compare it to Lewis and Clark: you go out and you never know what you’re going

to find. You could go out and nothing happens and you have a nice enjoyable day.

And you could go out and have all hell break loose.

The future of the tracks is wide

open. Perhaps in a few years, trains will haul coal again, or limestone, or

perhaps the tracks will close forever. For the time being, the tracks through

the Shavers Fork are in good hands and getting good use.

Looking across the ‘Big Cut’ as a train pulls up.

This was originally supposed to be a tunnel, but the Shale roof wouldn’t support

the weight so they simply cut the whole bit out. The shale continues to be a

problem as it isn’t stable and falls on the tracks periodically.

Photo courtesy

Keith Metheny from his grandfather, Clair Metheny.

Link to

Chapter Six

simultaneously attack. However, one of

the regiments encountered a supply wagon and the element of surprise was

lost. Due to the density

of the woods, neither side could estimate the size of the other force,

and 200 Union troops managed to rout the

1,500 Confederate soldiers. Over the next two days numerous skirmishes

occurred, but a coordinated attack was impossible and Cheat Summit Fort

withstood the attack.

simultaneously attack. However, one of

the regiments encountered a supply wagon and the element of surprise was

lost. Due to the density

of the woods, neither side could estimate the size of the other force,

and 200 Union troops managed to rout the

1,500 Confederate soldiers. Over the next two days numerous skirmishes

occurred, but a coordinated attack was impossible and Cheat Summit Fort

withstood the attack.

happy-go-lucky natures and pleasant dispositions. These laborers are the unsung

heroes of the industrial revolution, working eleven-hour days, six days a week

for just a dollar a day plus room and board. Amazingly, on this small amount,

many were able to later send money for their families to come join them in

America.

happy-go-lucky natures and pleasant dispositions. These laborers are the unsung

heroes of the industrial revolution, working eleven-hour days, six days a week

for just a dollar a day plus room and board. Amazingly, on this small amount,

many were able to later send money for their families to come join them in

America.

He walks over—we hadn’t

started into the tunnel yet—and he said, “You’re not going to have any problem

with this.”

He walks over—we hadn’t

started into the tunnel yet—and he said, “You’re not going to have any problem

with this.”

The passengers had a

real good show watching us with steel line bars and jacks pushing this thing

over. We just made the decision that the whole thing was unsafe. Of course, we

turned around, and everyone was still happy. No one asked for their money back

or anything. I don’t want to say we’re not in this for money because if we don’t

make a profit, it doesn’t happen. But like I said, we all want to see something

done to improve the area.

The passengers had a

real good show watching us with steel line bars and jacks pushing this thing

over. We just made the decision that the whole thing was unsafe. Of course, we

turned around, and everyone was still happy. No one asked for their money back

or anything. I don’t want to say we’re not in this for money because if we don’t

make a profit, it doesn’t happen. But like I said, we all want to see something

done to improve the area.